New Arrival !

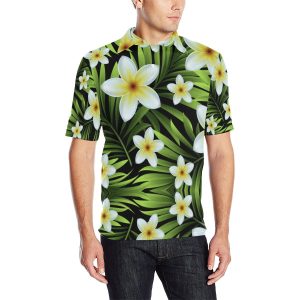

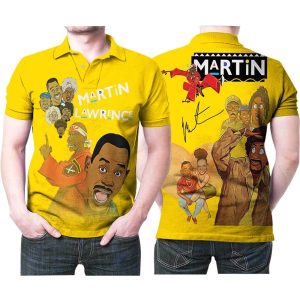

Polo Shirt

$44.98

$44.98

Personalized

$44.98

$44.98

$44.98

Polo Shirt

$44.98

Polo Shirt

$44.98

$44.98

$44.98

Polo Shirt

$44.98

$44.98

Polo Shirt

$44.98

Best Selling

$44.98

Polo Shirt

$44.98

$44.98

$44.98

$44.98

$44.98

$44.98

$44.98

$44.98

$44.98

$44.98

$44.98

$44.98

$44.98